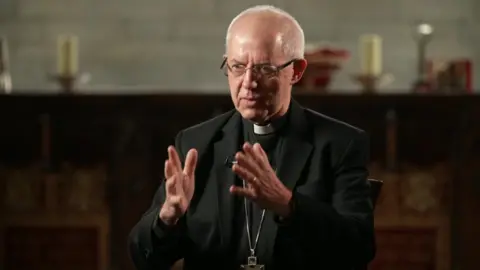

Welby says assisted dying bill ‘dangerous’

BBCThe Archbishop of Canterbury has called the idea of assisted dying "dangerous" and suggested it would lead to a “slippery slope” where more people would feel compelled to have their life ended medically.

BBCThe Archbishop of Canterbury has called the idea of assisted dying "dangerous" and suggested it would lead to a “slippery slope” where more people would feel compelled to have their life ended medically.

The head of the Church of England was speaking with the BBC ahead of the first reading in parliament of a bill that would give terminally ill people in England and Wales the right to end their lives.

Archbishop Welby talked of being unconcerned that opinion polls suggest that, on this issue, the Church of England more broadly is considerably out of step with the public as a whole.

Labour MP Kim Leadbeater, who introduces her assisted dying bill to Parliament on Wednesday, told BBC Newsnight she disagreed with the archbishop's "slippery slope" criticism of assisted dying.

What is the law on assisted suicide and euthanasia?MPs to get first vote on assisted dying for nine yearsSecular groups in the UK have long called for religion to be removed from the assisted dying debate and even for senior bishops to lose their right to sit in the House of Lords where they can vote on the matter.

“For 30 years as a priest I've sat with people at their bedside. And people have said, ‘I want my mum, I want my daughter, I want my brother to go because this is so horrible,'” said the Archbishop of Canterbury.

Justin Welby said that he did not want people to feel guilty for having such thoughts, saying that as a teenager he had sometimes harboured similar thoughts about his own father in the final years of his life.

“What I'm saying is that introducing this legislation opens the way to it broadening out such that people who are not in that situation [terminally ill] asking for this, or feeling pressured to ask for it,” he said.

The archbishop also referred to the death last year of his mother Jane, 93, saying she had described feeling like she was a “burden”. He said he worried how many others would feel compelled to ask to die if they felt the same.

Archbishop Welby said he had noted a marked degradation in his lifetime of the idea that “everyone, however useful they are, is of equal worth to society”, saying the disabled, ill and elderly were often overlooked in a way that would have an impact on whether they might access assisted dying.

One of his recent predecessors as Archbishop of Canterbury, Lord George Carey, is one of the most prominent Anglican voices who is in support of the legalisation of assisted dying.

But the last time assisted dying was voted on at General Synod in 2022, only 7% of the Church of England’s national assembly said they supported a change in the law.

In comparison, public opinion polls conducted over recent years in the UK have regularly indicated support for legalisation of assisted dying with majorities recorded in the 60-75% range.

“There will be people who look at that and say the Church is totally out of touch, that they totally disagree with us, and say they are going nowhere near a church, but we don't do things on the basis of opinion polls,” said the Archbishop of Canterbury.

Last week Cardinal Vincent Nichols, head of the Catholic Church in England and Wales, urged Catholics to write to their MPs to express their opposition to assisted dying.

But it is the Church of England that also has the privilege of being the “established Church” in England, and it is 26 Church of England bishops and archbishops who automatically get seats in the House of Lords and vote on legislation.

Assisted dying has already been one of the main issues where, for secular groups, that presence in parliament and influence over matters of state has been brought into question.

Ahead of introducing her assisted dying bill to Parliament, Kim Leadbeater told Victoria Derbyshire on BBC Newsnight: "There needs to be medical safeguarding and also judicial safeguarding."

"There has to be a change in the law. I'm very clear about that. But we've got to get the detail right. And, for me, this is about terminally ill people. This is not about people with disabilities. It's not about people with mental health conditions. It is very much about terminally ill people," she added.

Getty Images

Getty Images